Exploring the Pros and Cons of Lean Construction

Table of Contents

Toggle [ad_1]

Lean construction is one of those evocative phrases that you hear getting thrown around a lot in industry circles. And yet, like the best of buzzwords, it’s unclear to what extent anyone actually knows what the heck it really means.

Don’t worry, though, we’ve got you covered.

In this article, we will explain what lean construction is and explore some of the history that led to its creation. Then we’ll sketch out some of the benefits of lean construction, dive into its core principles, and provide a few resources for those who want to learn more. Finally, we will cast a critical eye on what has become one of the most popular business strategies in the construction world.

What’s Inside

What Is Lean Construction? Lean Construction Definition

The quick-and-dirty explanation is that lean construction is an approach to the business of building things that aims to minimize waste and maximize value for all stakeholders.

The idea is open to interpretation and has many different shades of meaning depending on where you approach it from. Some of its originators defined lean construction as:

“…a way to design production systems to minimize waste of materials, time, and effort in order to generate the maximum possible amount of value.”

But as pointed out in a 2018 paper on the subject: A single shared definition for lean construction has yet to be arrived at, and remains a bone of contention between academics focused on theoretic rigor and professionals who work in the field.

The weeds are definitely there to dive into, but we need not get lost in them…not yet, anyway. All you need to know for now is that lean construction is a guiding philosophy that seeks to improve every step of the building process, with particular focus on efficiency and the reduction of waste. Critically, this is achieved by changing the culture and having respect for the contributions of all involved.

Lean Construction Examples

Perhaps the most prominent examples of lean production in the building trade are offsite construction, as well as its offshoots, modular and prefabricated construction, all of which have successfully replicated the factory floor style manufacturing process of auto-companies.

Using a comprehensive project management system in concert with lean construction techniques can help deliver on the lean construction principles (e.g., improved project visibility, timeliness, and better outcomes).

Examples of lean construction tools and technology include:

As with big data, leveraging the copious quantities of project data available and, critically, connecting these data sources is key to delivering improved outcomes.

What Is the History of Lean Construction?

Lean construction first hit the scene in the 1990s. Its founders billed it as an alternative to “conventional construction”, which they characterized as a dysfunctional dynamic between siloed departments working at cross purposes.

The influence of the auto-industry on lean construction

Lean construction was inspired by the Just-In-Time (JIT) manufacturing method, which was itself influenced in part by Taylorism and Ford’s assembly lines.

Early Ford assembly line. Image source

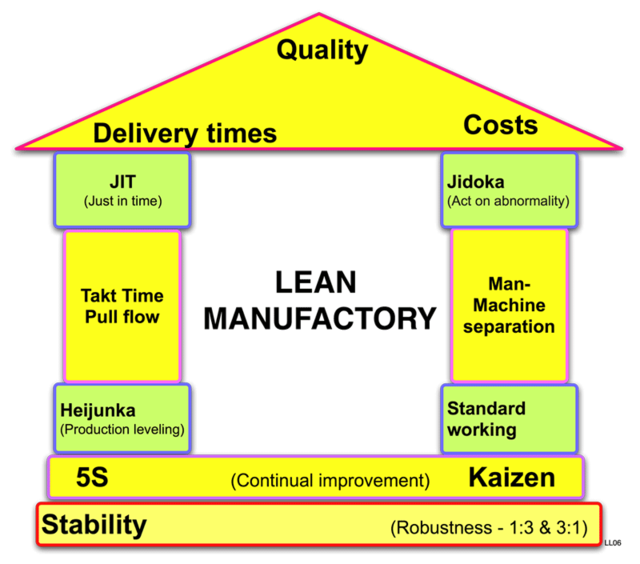

JIT was pioneered by the Toyota car company in the first half of the 20th Century. Just one part of the Toyota Production System, JTT is often associated with the Toyota Production System. JIT is an efficiency-focused approach that can be summed up as making only “what is needed, when it is needed, and in the amount needed.”

Image Source: WikiCommons

Renowned worldwide, JIT can now be found in industries across the globe, and has evolved into a popular inventory management strategy that aims to eliminate the need for safety stocks (resources held in reserve) by scheduling the arrival of materials and products “just in time” to meet customer demand.

Perfected in post-World War 2 Japan and widely implemented across Toyota’s auto-manufacturing plants during the oil crisis of the early 1970s, JIT’s focus on waste reduction, machine assisted workflows, and a continuous stream of process improvements (kaizen) sparked a revolution in thought about systems of production.

The arrival of lean construction

Having noticed Toyota’s success with the method, JIT began to take off in Western industries, eventually crystalizing into the idea of “lean manufacturing” in the 1990s.

The minting of “lean construction” as an idea came soon after and is widely credited to Lauri Koskela. A construction researcher based out of the United Kingdom, Koskela first wrote about the need for a paradigm shift in the world of construction in 1992.

For the early thinkers (namely Koskela, Glenn Ballard, Greg Howell, and Iris Tommelein), construction was in need of a coherent “theory of production” that focused on three primary elements: the transformation of materials into final products, the continuous and efficient flow of the construction process, and the creation of value for customers by eliminating as much waste as possible.

This theory of production was eventually given the name “lean construction.”

What Are the Benefits of Lean Construction?

Lean construction aims to provide a blueprint for building professionals to predict the behavior of production systems and instill greater efficiency into their businesses. It is less a prescriptive set of concrete techniques and more a mindset that must be cultivated and practiced over time.

This lean construction mindset is built upon discrete principles that, proponents claim, can be transformed into practices that yield beneficial results. Building professionals who follow lean construction principles can, for example:

- Minimize waste.

- Reduce expenses.

- Boost productivity.

- Improve quality over time.

- Increase value for the customer.

LCI’s model also includes showing respect for people, which increases ownership and transforms the culture.

That all sounds great, but what exactly are these principles of lean construction?

The Core Principles of Lean Construction

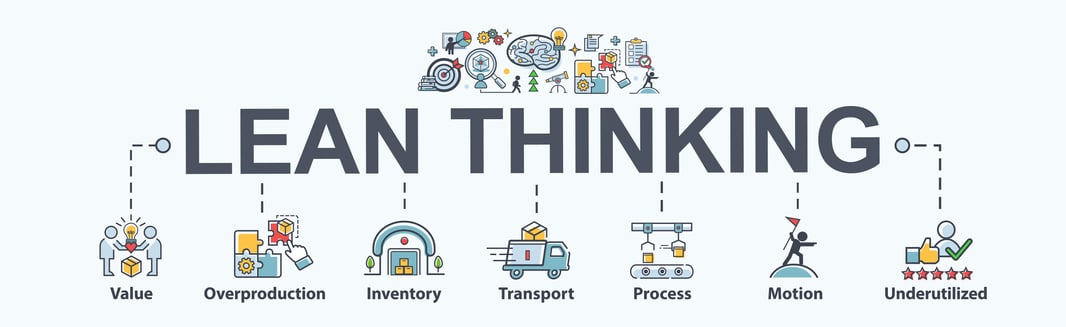

The concept of “leanness” is the subject of a wealth of writings online, most of which center on the importance of process improvements and waste removal.

A canonical set of lean construction standards remains a “work in progress” as Koskela et al. put it, but there are several different sources that outline helpful lean principles for building professionals to follow.

For example, in Chapter 4 of the book “Transforming Design and Construction”, the Lean Construction Institute lays out four core principles that practitioners of lean construction should adhere to:

- Continuous Improvement: This is the Japanese idea of kaizen, which translates roughly to “change for the better”. Above all, practitioners of lean construction must adopt the mindset that every process, no matter how streamlined, can be continuously improved upon. Experimentation in the name of process improvement should therefore be encouraged, as it will likely lead to increased value.

- Removal of Waste: Always be watchful for ways to identify and remove waste from the building process. Waste can come in many forms, whether in the utilization of resources or the allocation of efforts by the workforce. Though waste isn’t always obvious, building professionals should always strive to eliminate any expenditure of resources or effort that do not add value to the construction project.

- Generation of Value: This is the idea that every resource should always be used to efficiently and correctly transform raw materials into the final built product. Ask yourself if every expenditure of a resource is in the service of adding value to the construction project for the customer.

- Focus on Process & Flow: Construction professionals should focus on the process by which materials and workflow together from one stage to the next. Creating a standardized process for teams to follow is an excellent way to ensure consistent outcomes over time.

Another oft circulated, albeit more generic set of lean principles can be found in the opening pages of the book “Lean Thinking” (1996) by James P. Womack and Daniel Jones.

We’ve adapted them below to fit into a more construction specific framework:

- Identify Value: Figure out what the customer wants. To practice lean construction, building professionals must first have an intimate understanding of what clients value. What is their price point? What kind of customer experience are they looking for? Are they interested in IoT amenities and smart innovations? Or do they value sustainability above all else? This type of knowledge grounds the building process in reality and provides a target to aim for. Achieving this level of understanding requires open dialogue with clients about what their expectations are for during every stage of a construction project.

- Map the Value Stream: Nail down the existing process. Once the value from the client’s point of view is understood, the next step is to map out every single step of the process by which that value is created. The act of assembling the building itself is of course an essential piece of this puzzle, but it’s not the only one you need to be mindful of. Every team member from the surveyors and inspectors all the way up to the architects and project managers plays a variety of important interconnected roles during the complex life cycle of a construction project. Practitioners of lean construction must understand how all these roles are interrelated and have a firm grasp of all the steps that are necessary (as well as those that are not) to shepherd a building project from the conceptual stage all the way to completion. In this way, inefficient steps or even entire processes can be identified as wasteful and trimmed from the equation.

- Create Flow: Change how you think about efficiency. Now that the value has been identified and the process by which it is created is mapped, practitioners of lean construction should strive to tear down the partitions between departments and design a system of production that flows continuously from one stage to the next. Departments that are siloed off from each other will always prioritize their individual missions over that of the whole. Greater efficiency can be achieved by putting separate teams into closer communication and seeking to more seamlessly integrate their processes in service of the overall mission.

- Empower Clients to Pull: Make it easier for the client to get what they want when they want it. With a flow-based process in place, the next step is to empower the client to “pull” or get their hands on their timeline instead of yours. This is the difference between “pushing” a product onto the customer that you only think they might want. By establishing pull, you can ensure that the client will always get what they are looking for out of a construction project “just in time”.

- Work Toward Perfection: Instill lean thinking into your company’s DNA. Completely retooling how you think about and approach the work of construction is only the beginning. The final stage is to make lean construction an indelible part of how you do business. This means embracing the fact that lean construction is not a system that’s frozen in a moment in time, but is a fluid interplay that requires revisiting and constant vigilance for ways to remove waste and improve processes from beginning to end.

Lean Construction Resources

Understanding lean principles is one thing, figuring out how to operationalize it is another thing entirely. For those interested in clearing that hurdle, we’ve assembled a short list of helpful tools and resources:

Criticisms of Lean Construction

Now that we have a clearer idea of what lean construction is, where it comes from, how it works, and how it can be introduced into the workplace, it’s time to take a look at some of the criticisms that have been leveled against it.

If you’re reading this in the early decades of the 21st Century, odds are that the lean mentality is all too familiar to you. “Doing more with less” has become the dominant axiom of our times, driving everything from healthcare administration to global economic policies. And as we’ve seen in recent years, the results aren’t always for the better.

Critical breakdowns in the global supply chain during the COVID-19 pandemic have largely been attributed to the failure of the Just-In-Time approach, prompting all kinds of industry players from healthcare to auto-manufacturing to reconsider their devotion to lean ideology.

To be clear, the globally embraced logic of efficiency that underlies “lean” and “do more with less” thinking has indeed led to increased productivity, as its originators claimed it would. The main problem, however, is that the cost of this increased productivity over the years has been thrown squarely on the shoulders of workers.

Nowhere is this cost more starkly illustrated perhaps than in the growing gap between productivity and pay. American workers in particular have never been more productive, and yet astonishingly, their wages have virtually plateaued since the 1980s. This gets at the root of many criticisms surrounding lean thinking: It prioritizes technical efficiency and the needs of industry over the health and safety of the human workforce.

The lean philosophy, critics argue, encourages industry leaders to cut corners and focus their search for waste in areas that inevitably harm workers. Flattened wages, layoffs, and lack of overtime pay are justified as cost-cutting measures–even when the company is experiencing record-breaking profits. Lengthened work days, shortened breaks, and the elimination of paid sick leave are introduced to squeeze more productivity out of an already over-extended workforce. Meanwhile, steep work quotas and employee tracking technologies are used to ensure that no time is wasted while on the job.

Are these examples of prudent waste removal? Or worker exploitation? The answer and the value you place upon it depends in large part on the angle from which you approach the issue.

Wherever you fall on the matter, questions about the human cost and the inherent tension between management and workers have been a part of the conversation around lean construction since the beginning.

Presented at the 7th conference of the International Group for Lean Construction in 1999, the paper “The Dark Side of Lean Construction” by Stuart D. Green, a professor of construction management, highlighted a variety of critiques; including the fact that the Just-In-Time method in Japan relied heavily on the exploitation of workers during a period of severely diminished labor rights.

Under the new lean regime of the 1970s, Japanese workers were often forced to work extremely long hours without days off. The successful introduction of lean production methods in the United States, Green argues, similarly relied on the disempowerment of American labor unions during the Reagan administration in the 1980s. While improvements have been made in recent years, the efficiency obsessed work culture in Japan grew so extreme over the ensuing decades that it birthed two new concepts to describe work-related stress: karoshi and karojisatsu, which translate respectively to “death by overwork” and “suicide by overwork.”

The human costs of overwork are hardly limited to Japan. A recently released study by the World Health Organization showed that overwork killed more than 745,000 people worldwide in 2016. The study went on to note that the stress from working more than 55 hours a week significantly increases the risk of stroke and heart disease; yet more than 488 million people worldwide routinely work well in excess of that amount. Overwork can also increase the rate of worker injuries by as much as 61%, another study found.

These kinds of outcomes are to be expected when critical thinking is jettisoned in favor of an excessive form of lean thinking that crowds out all other considerations. On the other hand, this could be due to improper application of lean principles, with many companies over the years having focused only on the tool side of the TPS while neglecting to understand the “people” side of the system.

We’ve said it before and we’ll say it again: above all else, safety must always be the number one priority in an occupation as hazardous as construction.

While the discipline associated with 5S, a lean tool, actually contributes to safety on jobsites, you have to wonder, is the selection and application of a few select tools that achieve short term wins or a systematic approach?

Bottom Line

Lean construction has a lot to offer for those who are interested in making their businesses less wasteful and more efficient. There’s a reason why the lean strategy has been so widely embraced since its early days on the factory floors of the Toyota manufacturing plants. By adopting lean principles, construction professionals can make significant strides in understanding and improving upon the workflows that lead to the creation of value for clients.

It’s important, however, to never lose sight of the human element. At the core of LCI’s lean tenets is “respect for people” Additionally, the Last Planner System is built around the belief of engaging the people close to the work to make decisions. Lean is truly a system that requires a disciplined approach to implement that can yield tremendous benefits to all involved. Just like in any other construction process, you have to build it in the right sequence.

[ad_2]

Source link