A retirement safe from climate change? Ask the tough questions about real estate and property insurance

Table of Contents

Toggle [ad_1]

The images were shocking: tidy rows of suburban houses ablaze as a wildfire ripped across the open prairie now populated by fast-growing Louisville, Colo., whose 20,000 residents are nestled perfectly between desirable Boulder and Denver. Some 1,000 homes were a total loss and tens of thousands of residents fled the deadly December fire that flared up unusually late in the season, kindled by a multiyear drought.

Earlier in 2021, days-long media coverage darkened with dwindling hope for survivors in a crumbled condominium tower in Surfside, Fla., just north of Miami. A confluence of factors was believed to be at the root of the collapse that claimed 98 lives, many of retirement age: delayed maintenance, outmoded code standards grandfathered in, plus the long-run effects of a higher water table and corrosion from salt water.

For many, it was a wake-up call that a densely developed south Florida — as well as Tampa and nearby communities on the Gulf side — were going to see building resilience tested over and over by global warming-linked coastal water rise. Residents must also consider the increased likelihood of extreme downpours as climate change intensifies typical weather incidents and expands their seasonality.

Yet plenty of observers bristled at the climate-change connection in Surfside because building factors and human error were present. It’s a reflection of how challenging it can be to push real world solutions for an existential risk like climate change. Who wants to think of a Floridian paradise, long a U.S. retirement destination and international tourism draw, in deeper peril than the standard hurricane watch?

The reality is, climate-change impact is already being felt. Natural disasters aren’t new, but their frequency and staying power are intensifying. And key sectors that factor into retirement considerations — real estate and insurance — are lagging in their preparation for a new-normal.

With each passing tornado, flood or forest fire, it is becoming increasingly clear that one of the best new ideas in retirement is protecting our homes from climate change. It will be costly, both financially and politically, and will need to include a sea change when it comes to how the insurance industry operates in a world in which 100-year weather events are happening every five years, and all over the country.

“This is one of the major systemic issues today: climate change is not being priced into housing,” said Raj Dosaj, head of real estate for Cape Analytics, which provides geospatial maps and property information. “In almost all areas with growing risks, most homeowners can still get affordable property insurance — in fact, many of these areas are naturally beautiful and, with the pandemic, have seen even faster home-price appreciation than other areas.”

Flexible work schedules during the height of COVID-19 pulled people out of heavily-populated areas to work at their own vacation homes or Airbnb-type rentals and workplace flexibility may be here to stay. Plus, what’s been billed as the “Great Resignation” during the pandemic lured some 4.3 million Americans from the workforce into retirement.

According to many experts, climate change poses a potentially dangerous future in some locations even if a warming atmosphere can be slowed by global efforts to swap high-emission oil and gas for solar, wind, hydrogen and nuclear power, and by incentives to eventually designate all gasoline-powered cars for scrap metal and replace them with electric vehicles, electric bicycles and improved public transportation. Some of the warming effects just can’t be reversed.

Members of the South Florida Urban Search and Rescue team look for possible survivors in the partially collapsed 12-story Champlain Towers South condo building in Surfside, Fla., in June 2021.

AFP via Getty Images

The good news is Americans can still imagine a scenic, active and secure retirement, but they need to factor climate change into their plans. Joseph Coughlin, founder and director of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology AgeLab, says that any message about climate-change preparedness has to empower retirees.

“It can’t be about washing away by the sea. It has to be: This is how you fight back, take control, be better prepared. At a certain age, people want to hear less about impending frailty than about how to maintain capability. Climate-change adaptation should be no different,” said Coughlin. The AgeLab he runs with graduate students examines aging and technology use by those aged 50-plus, which includes Generation X and boomers.

Prepared would-be retirees should be asking — and the service industries must be able to answer — what type of housing will be safest from extreme weather, fire and power outages? Can I be insured on a coast? In a flood zone? If I qualify, can I afford that property insurance? What if I have to flee danger quickly? Can I enjoy the outdoors most days of the year? Can the indoors be cooled without breaking the bank?

Be informed: What does science tell us?

Every summer, from Miami to Cape Hatteras, N.C., people prepare for a possible hurricane. Residents get ready to shelter in place behind hurricane-grade windows or pack an overnight bag and crate up their pets to flee via a designated route to safety. When big storms do hit, which they tend to do every five to seven years, television broadcasters rapidly descend to cover the chaos and damage. They usually find some displaced or impacted retirees to interview.

“As NASA and other valuable agencies tell us, evidence is emerging linking climate change to extreme weather, such as hurricanes and storms most assuredly affecting favorite coastal warm-weather retirement destinations,” said AgeLab’s Coughlin.

But it’s not just hurricane alley and all its press coverage that bear watching. Rising waters are impacting retirement destinations favored by empty-nesting urban downsizers on waterfronts as far north as New England, or even Nova Scotia.

And looking inland, more than 13% of the U.S. population currently resides in the 100-year flood plain. That number could rise to 15.8% by 2050 and 16.8% by 2100, according to a study largely critical of underreporting in current Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) mapping, addressed in a commentary by the Yale School of the Environment.

If it’s not rising water that’s raising concerns, it certainly is an expanding tinder box. A report by the United Nations Environment Program estimates that with even moderate temperature increases, the number of extreme wildfires globally will increase by as much as 30% by midcentury and 50% by 2100.

Severe weather can also bring harm even if it doesn’t leave lasting property damage. Government data analyzed by the Associated Press showed power outages tied to severe weather rose from about 50 annually nationwide in the early 2000s to more than 100 annually on average over the past five years, according to electricity disturbance data submitted by utilities to the U.S. Department of Energy. Blackouts can impact medical care at home, limit our ability to preserve food and generally, spoil the ability to enjoy an active retirement. U.S. power customers on average experienced more than eight hours of outages in 2020. And creating your own power is a cost consideration; generators can run anywhere from $4,000 to $20,000, said AgeLab’s Coughlin.

Real estate: Buyers should ask climate-change questions

Forbes, one of many publications that issue ever-popular home-buying destination lists, now factors climate risk into its annual roundup of 25 retirement dream towns. But online search companies, such as Zillow, Redfin and Trulia, have been slow to alert for flood risk or other potential red-flags on listings. Realtor.com broke with that tendency, adding flood data in 2020 and wildfire data, compiled by nonprofit First Street, this year.

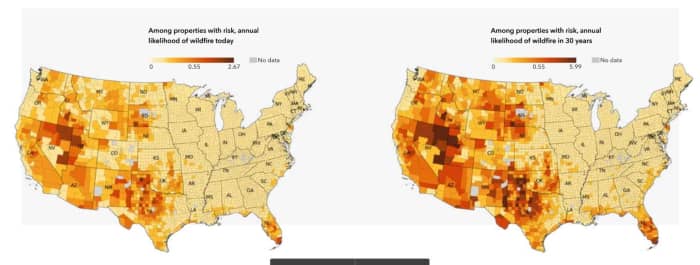

The First Street/Realtor.com tool and accompanying report finds that as many as 20 million properties in the lower 48 states face “moderate” risk, or up to a 6% chance of experiencing a wildfire over 30 years, essentially the life of the most popular mortgage. And unlike the typically narrow one-year window used in present-day insurance pricing, the wildfire tool assesses the risk to homes and commercial buildings from damaging wildfires if they struck right now, and up to 30 years in the future.

On the left, darkened areas show increased risk of wildfires currently. On the right, even darker areas, and more widespread, show the increased annual likelihood of wildfire in 30 years.

First Street Foundation

Real estate agents, mortgage lenders and other professionals in the industry believe buyers aren’t asking enough climate-change questions, especially if they plan to stay in a property for years — and the industry isn’t feeling compelled to disclose much either.

Risa Palm, professor of Urban Studies and Public Health at Georgia State University, and her colleague in the political science department, Toby Bolsen, wrote in a commentary of their efforts to log real estate dedication to climate-change information.

The duo surveyed 680 licensed Florida real estate agents in late 2020. Their responses suggest that prospective home buyers are not routinely taking elevation or flood vulnerability into account when searching for new homes, and the availability of improved flood risk maps has had little or no impact on them.

“Part of the problem may be that mortgage lenders and appraisers aren’t accounting for properties’ vulnerability to sea level rise, so home buyers aren’t immediately feeling the risk in their pocketbooks,” Palm and Bolsen say. “Wealthier buyers who don’t need a mortgage [and make a cash purchase] aren’t required to purchase flood insurance, and Congress has a history of rolling back flood insurance rate increases.”

It’s true that many factors impact housing prices. Even though California experienced five of the state’s six largest wildfires in state history in 2020, overall housing demand meant that even devastated wildfire communities experienced jumps in home prices, a phenomenon that some said only puts more people in harm’s way since there’s little incentive to take preventive fire measures.

A broader 2020 analysis from Realtor.com showed that home buyers were only beginning to factor concerns about climate change into their decision-making. As a result, homes in areas vulnerable to fires and floods could see weaker price growth, but the discount wasn’t dramatic, economists at the trade group say.

For buyers, risk assessment may be abstract and overwhelming, which is why the professionals need to be more reliable.

“When it comes to location, the physical impacts are changing with climate change, but they’re changing at different rates, in different directions, in different places, that are not well understood by most people. Maybe Miami looks better than Phoenix for your heat sensitivity. Maybe Dubai looks better than either,” said Rich Sorkin, CEO of climate analytics provider Jupiter Intelligence.

”The second factor when it comes to retirement and climate change is this concept of duration mismatch … the information that people are looking at is the wrong time horizon for the decision they’re making. It’s like looking at a potential partner at 18 years old. And reassessing that partner at 48. Maybe not such a great match,” he said.

Robert Heck, vice president of mortgage with Morty, an online mortgage marketplace headquartered in California, agreed that the real estate industry is a slow adapter to climate risks.

“We’ve yet to really see lenders barring certain areas of the country specifically due to climate change from financing,” Heck said. “We see it in some markets for homeowners insurance — I’m in Lake Tahoe in California and we’ve lost a lot of policy underwriting due to drought and fire — and that can circle back and impact mortgage approval, but it’s a bit indirect.“

“We try to help retired clients navigate all the ongoing costs — and climate change factors should be in there — especially as homeowners will want to make retirement savings stretch as long as possible,” Heck said. “Should they look at a smaller home? Should they reconsider location? We want to walk them through all of it.”

Insurance: a reckoning in the making

Led by the deadly and costly Hurricane Ida in the U.S.and massive flooding in Europe, the world racked up $329 billion in economic losses linked to severe weather in 2021, and only 38% of that bill was covered by insurance.

Further, even when insurance can be counted on, its actuarial scope falls short when it comes to climate change. Property insurance is based on one-year risk calculations, looking back to the year just completed.The formula doesn’t work well as a proxy for risk for longer-term assets, including homes, when the risk has intensified to the degree that climate change presents.

“I believe that insurance is broken and you can quote me on that,” said Jupiter’s Sorkin.

“Either the insurance industry writ large is going to evolve and start accounting for these future risks,” he added. “Or, there will be a divergence: One side will say we don’t believe the climate change you are describing is ‘material’ to us. Or, one side says, yes, it’s a big deal, but we don’t have control over our own analytics and workflows. Either way, there are potential cost issues for consumers — costs will go up.”

A woman walks along a flooded street caused by a king tide in Miami Beach, Fla. While higher seas cause much more damage when storms such as hurricanes hit the coast, it doesn’t always require a big storm to create flooding. High tides get larger and water flows further inland and deeper even on sunny days.

AP

Insurance evolution may be evident in some places, but typically at a shocking price jump for consumers. That’s already happening in Florida, for instance, where many traditional insurance names have pulled out, in part due to a flurry of litigation to force insurers to pay more. But the exodus has reached a point where some who regularly cover the sector venture to call it a “crisis.”

Instead, specialty insurers known as excess and surplus (E&S) carriers push into these areas. They take on extra risk and often are licensed outside the state where standard insurers have left. For consumers, that may mean the chance to buy insurance when they otherwise could not, although at a higher cost, In some ways, the specialty premium may help better assign risk to the most disaster-prone areas.

The industry is also trying to creatively solve for the unknown that comes with climate change.

Though it remains a small part of the market, parametric insurance has gathered increasing interest. Unlike traditional casualty insurance that reimburses a policyholder for the cost of damage incurred to property, parametric insurance covers the probability of some event happening that is likely to cause an economic loss.

And perhaps the biggest change to date comes from the federal flood insurance program, which is also attempting to update its flood-zone maps.

Flood damage is excluded from standard homeowner’s insurance policies, yet only 15% of American homeowners had a flood insurance policy as of 2018, according to the Insurance Information Institute.

What’s more, flood insurance is handled with a government program, not private issuers, although with a few exceptions.

The government program has faced its own changes — changes long in coming, say experts. Saddled with more than $20 billion in debt from hurricane payouts, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) National Flood Insurance Program raised premiums in 2020 by an average of 11.3%, and higher for properties in the most flood-prone zones. With the increase came the first overhaul of the system — called Risk Rating 2.0 — since the inception of the program in 1968.

That Fine Print Matters More than Ever

Homeowners face potential tests to the scope of their insurance coverage already, and climate change will only add to the challenge, said Brian Patillo, vice president of Goosehead Insurance, an independent brokerage which compares several carriers to find the best fit for an individual policy-holder.

For instance, many homeowners, wary of premiums and deductibles when balancing other household expenses, may have a policy that covers only up to a portion of the replacement value of their home. Perhaps that amount was set based on purchase price and what the insured person might be able to afford monthly. But home values, material costs and construction labor may have risen since the home was purchased: a policy that maxes out at $400,000 won’t cover the exact rebuilding of a destroyed home that will now cost $550,000. This, in fact, was the case when wildfire struck the popular Louisville, Colo., where rebuilding prices had also jumped during a global materials supply shortage and a post-COVID inflationary surge for many segments of the economy.

Allison Price digs through the debris at her boyfriend’s parents’ house in a neighborhood decimated by the Marshall Fire in Louisville, Colo. Officials reported that 991 homes were destroyed in the fire that sparked around the New Year holiday, making it the most destructive wildfire in Colorado history.

Getty Images

For Steve Bowen, a meteorologist and head of catastrophe insight at Aon, a consulting firm for the insurance and reinsurance industry, climate change is already widening the insured vs. uninsured or underinsured gap in the U.S.

Surveys from the research firm Marshall & Swift/Boeckh have found about 60% of homeowners nationwide are underinsured by approximately 17% of the cost of their home. A quick number crunch reveals they would be short about $34,000 on the average national home price of $200,000.

“If you have a career pension or 401(k), likely you’ll be able to handle more robust insurance demands,” Bowen said. “But there is a non-negligible portion of current retirees or those close to retirement age who simply don’t have enough money to retire, yet alone have enough insurance in retirement. We saw that after the fire in Paradise, California.”

It’s also true, he says, that where there are insurance shortcomings, there can be a hit to property values. An adequately-insured home can make a claim against individual damage. But if most dwellings on a street or in a neighborhood never snap back from devastation, even the repaired homes’ potential resale values are hit. Remember: location, location, location.

A man rides a bicycle through a flooded street after Hurricane Isaias blew through popular retirement destination Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, in August 2020.

Getty Images

How else can retirees prepare?

Ask, don’t assume

As consumers gear up for retirement, they should reach out to their insurance agent to confirm coverage for the natural disasters they may encounter in the area they plan to settle down in. “For instance, damage from floods and earthquakes is not typically covered on a homeowners policy, so working with an independent agent to assess those risks and purchase the right coverage is crucial for their successful retirement,” said Goosehead’s Patillo.

Consider renting, not buying right away

Renting may allow you to not only get a feel for your retirement selection, but to get a handle on the managing of your finances and whether added property insurance costs are necessary and will be worth it.

The data is there, and improving

Companies like Cape and Jupiter and others are helping communities understand and adapt to the changing climate front. You can look up select data yourself, including FEMA’s new map for natural hazards. Insurer The Hartford and MIT’s AgeLab collaborated on an awareness campaign for seniors and disasters.

An emergency plan is vital

Protecting your property is one thing, saving your life is another. AgeLab’s Coughlin warns that even the cities most ahead of planning for climate-related disasters, and those in hurricane paths that already take such steps, aren’t very good at ensuring their most vulnerable citizens, such as seniors with mobility issues, can also flee to safety. Research and a plan for how you might head to safer ground if necessary must factor in your preparedness for a safer retirement.

Protect your property from day one

Can you take steps out of the gate to limit disaster? California, for instance, has a statewide code for its wildland-urban interface areas that includes details such as how far trees and shrubs should be kept away from homes, and construction materials to use that can help protect homes within a fire hazard zone. Not all states provide that guidance, though. Colorado lawmakers rejected recommendations for a statewide code in 2014, leaving it up to each county. Ask how your county or city handles these codes. There are International Code Council and National Fire Protection Association wildland-urban interface fire codes that can be adjusted to local conditions.

Most codes and the insurance industry suggest the roof of a home be made of fire-resistive Class A materials, such as asphalt shingles or concrete tiles. Walls are rated based on the duration of time they can withstand fire. Researchers are also trying to commercialize exterior sprinklers that don’t require electricity, large fire blankets that can cover a house and fire-retardant foam that can be sprayed on structures.

As for severe wind, metal roofs — considered better able to withstand high gusts — are increasingly in demand. Finally, if you’re in a flood zone, consider moving utility equipment out of the basement to a spot above ground.

Don’t forget about extreme heat

Plan for more hot days if you opt for a region already featuring warm summers. Previous extreme heat waves in Chicago, for example, proved deadly to older residents in particular. The same can be said for the Pacific Northwest in summer 2021, which led to an overflow of cooling centers for a region with historically mild summers.

For many places, air conditioning, once used only for a few days a year, is now used for a few months and can be an unplanned retirement expense, said the AgeLab’s Coughlin. Your air-conditioning unit may need to be replaced with a more efficient model as average temperatures rise.

A battery-run power generator may be a must-have addition. Many people are already taking action; spending on generators rose 36% between 2016 and 2019, The Wall Street Journal reported.

Think resiliency now, not later

For Cape’s Dosaj, it could be too little, too late for retirees if they’re scrambling to react to climate change rather than anticipating these risks.

Foresight from the real estate, construction, planning and insurance industries, alongside state and federal governments who have a role in protecting retirees, is what’s needed, he says.

“I see risk mitigation — helping homeowners build less-vulnerable, more-resilient structures to the hazards they may face — as the best way to keep communities safer but also minimize the potential rising costs of buying, selling and insuring a property,” said Dosaj.

“This is the best overall bet as it reduces risk across the system. Government subsidies and programs to retrofit homes in high risk areas — like the federal government is beginning to support in wildfire areas — may come increasingly into play,” he said. “As these needs increase, it will be up to taxpayers to support the move to a more resilient housing stock.”

[ad_2]

Source link